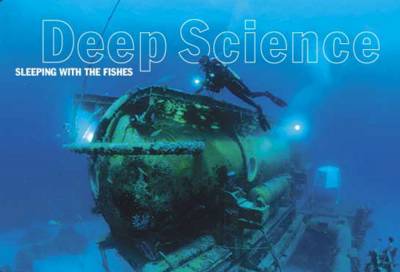

We were 85 feet (26 meters) underwater and more than five miles (eight kilometers) off the Florida coast when the lights went out. It was night, and conservationist Craig Taylor and I had been diving for two hours by the dim beams of the Aquarius research station—our underwater home and, at that depth, our only safe haven. About the size of a railroad freight car, Aquarius looked like a spaceship on the seafloor, an interior glow filling her view ports, exterior spotlights illuminating her sides and legs. When she lost power, she simply disappeared into the inky blackness, and I felt as cut off from the world as an astronaut stranded in space.

I fought the impulse to head for the surface, which is what scuba divers are trained to do when they get into trouble, because this was no ordinary dive. For the past four days we'd been living in Aquarius as aquanauts, and by now our bodies were saturated with nitrogen. If I surfaced quickly, without decompression, dissolved nitrogen in my body would expand from the sharp decrease in pressure, forming bubbles that could painfully squeeze nerves, block blood flow, or cause brain damage. Decompression sickness probably would kill me.

Suddenly Aquarius's emergency siren started wailing—a signal for all aquanauts to return immediately. The piercing sound, however, seemed to come from all directions. Breathing heavily on my scuba tanks as I swam through the darkness, I used my emergency lights to search for the web of excursion lines that had been mapped out for us during our one-week training session. These guidelines were a safety measure to help us navigate around the reef. Grasping a black braided rope in one gloved hand, Craig and I followed the line back to the station, where we felt our way across the coral-and-algae-covered metal to the rectangular opening in the bottom known as the moon pool.

The station functions like an inverted glass pushed down into a bucket of water: An air pocket remains at the top of the glass while the glass remains upright. The crew maintains the air pressure inside Aquarius at the same high pressure as the surrounding ocean, keeping the water from rushing in. We lived in that air pocket, which I was eager to get back to. Emerging from the ocean water, I stood waist-deep in the moon pool, removed my regulator, and breathed in the hot, humid air from Aquarius.

"Generator's down," said Christian Petersen, a U.S. Navy diving medical officer, as he stood above me in the dim emergency lighting. Without power from either of the two electric generators in the life-support buoy tethered above us on the surface, we had only dim emergency lights and no air-conditioning. In these warm tropical waters, with a half dozen people inside, our small laboratory would rapidly become stifling. I climbed up the stainless steel steps, peeled off my dive gear, and began to sweat.